Writerly Play Kit 006 – Structuring Ideas

Writerly Play Kit: 006

Structure Your Ideas With Style

WP Kit: 006

Structure Your Ideas with Style

Whether you’re a plotter or a pantser, the ability to step back and take a 30,000 foot view look at your project is essential. Whether you’re planning a new book, setting goals, or re-envisioning your office, there comes a point when you must think strategically … or accept the fact that you’re going to lose a lot of time wandering in the land of indecision.

Recently, I heard Brooke Castillo explain the need for strategic thinking in this way. Imagine you’re riding your bicycle somewhere far across town. You need to arrive where you’re headed urgently, so you pedal, pedal, pedal. But what if you took the time to get off the bike, climbed into your car, and fired up the GPS?

Sometimes we’re so committed to moving forward that we don’t stop to think about what might work more efficiently. Or, alternatively, we might resist strategic thinking because that’s not our biggest strength. Just as learning to be more playful in our thinking is key across every creative style, learning to be more strategic is important as well.

In this Writerly Play Kit, we’ll explore critical thinking tools and strategies that we can use to structure our stories, develop our ideas, and revise our lives and work.

Featured articles

CREATIVE LIFE

HOW TO reach a complex goal

Many writers spend a lot of time in their mental “Workshop,” structuring their stories, developing their writing craft, and revising their work. However, we may not apply those same cognitive skills to our careers and lives. Whether we’re storyboarding a work of fiction or our actual lives, the strategic thinking involved uses the same mental muscles.

Do you have an exciting (and complex) goal? Let’s put those powerful mental muscles to work to figure out how to travel from where you are now to that big dream.

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

-Albert Einstein

The Writerly Play WORKSHOP

Activities

Storyboard Like a Detective

FOR INVENTORS

Define the scenario, collect clues, and ultimately, resolve your questions. Capture your thinking on your storyboard.

Storyboard Like an Animator

FOR COLLABORATORS

Use the Hero’s Journey to structure your storyboard discussion with a collaborator.

Storyboard Like a Reporter

FOR ARCHITECTS

Structure your thinking about a project with a reporter’s questions. Use your discoveries to shape your storyboard.

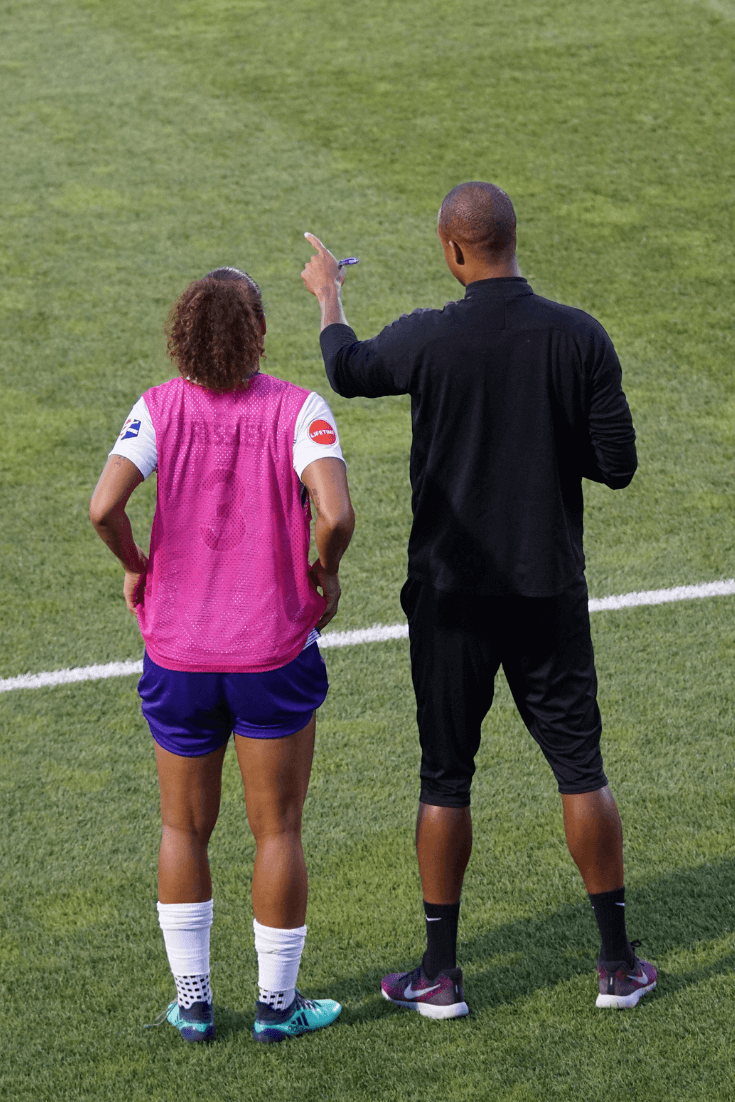

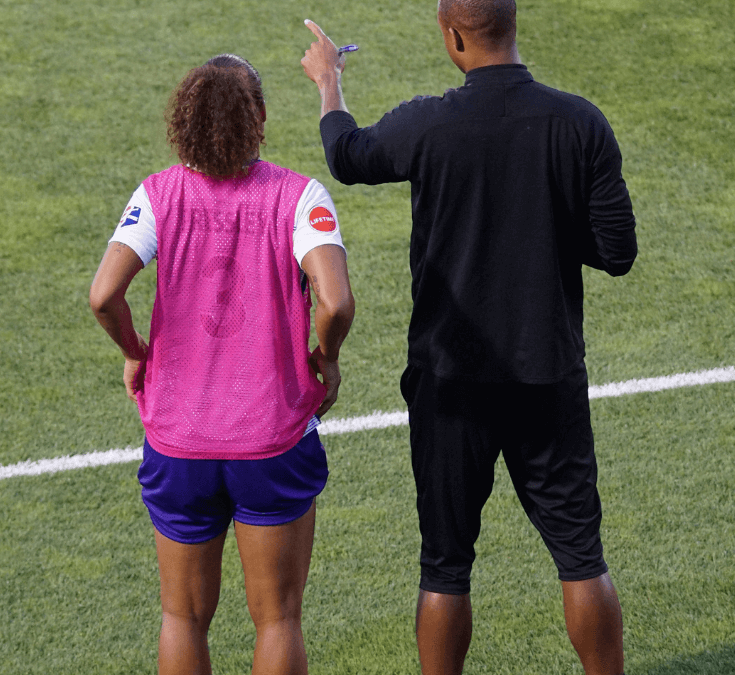

Storyboard Like a Coach

FOR SPECIAL AGENTS

Run a few quick scenarios for your idea and then choose a game plan for your storyboard.

Wondering what Writerly Play is all about?

Writerly Play is designed to help you make the most of your creative potential. Each Writerly Play Kit is designed to help you stretch your thinking skills and develop practical strategies perfectly fit for you.

Want a shortcut? If you don’t have time to read today, but want a quick win, try this quick quiz to identify your creative strengths and weaknesses:

Once you know what works best for you, you need a perfect-for-you plan. Writerly Play functions more like a map rather than a cookie-cutter recipe. First, you’ll locate yourself on the map. Then, with a clear understanding of where you are, you can make informed choices about your next best steps.